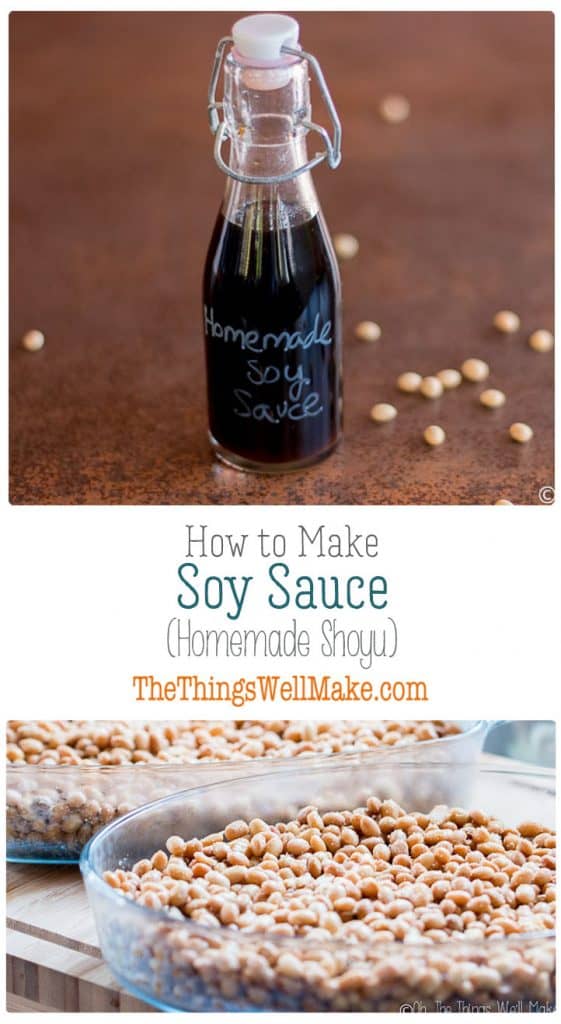

Impress your friends and save money by making your own soy sauce from scratch. Today we’ll learn how to make a homemade shoyu, a fermented soy sauce made from soybeans and wheat berries.

This post has been in the making for several years now. Yes, years!

I’ve had several failed attempts before finally reaching success and making a wonderful soy sauce with complex flavors. Fortunately, my failures were due to misinformation more than they were to a complicated process. Making your own soy sauce does require some patience, but it really isn’t that difficult.

When I first started trying to make my own soy sauce, there wasn’t a lot of information on the web, and the only posts about the process showed people making patties out of soy and letting them grow mold from whatever wild molds might be present in the air. Many of these “recipes” were based on people watching their Asian relatives make soy sauce at home. I guess the whole process sounded a bit risky, but since it’s quite common for people to make sourdough starters from the wild yeasts in the air, I thought the idea had some merit and decided to give it a try. (I mean soy sauce making had to start somewhere, right?)

The problem?

Making soy sauce is a long process, and each time you give it a failed shot, you end up wasting a lot of time.

I tried making a homemade soy sauce with local wild molds, and while trying it didn’t kill me, it didn’t impress me either. Maybe it has something to do with the fact that the wild molds and yeasts here in Spain are different than those in the soy sauce making regions of Asia. (From a bit of further research, it appears that making soy patties that collect local molds is most typical in Korean soy sauce making.)

The process of making it wasn’t easy sailing either. I had to endure foul-smelling moldy soy patties (not to mention my husband’s complaints about the odor.)

We’ll just say that my first homemade soy sauce wasn’t good enough to share on the blog. Just as sourdough starters will vary from region to region, not only can a wildly propagated soy sauce have a lot of variances, but it could be potentially dangerous. That’s why you need to start with a specific fungus for inoculating your batch. Luckily, using a starter fungus also makes for a much more pleasant soy sauce making experience. (Yes, it smells much better too!)

Watch How to Make Soy Sauce (Homemade Shoyu)

What is Soy Sauce?

Soy sauce is a thin, liquidy, Asian condiment normally made from fermented soybeans. Specific strains of fungus are grown on soybeans, and then the mixture of fermented soybeans is allowed to continue to ferment within a salt brine.

Soy sauce varieties vary from region to region, and not all modern day soy sauces are actually even fermented anymore. Most store-bought soy sauce will be pasteurized, too, so it’s great to be able to make your own and add one more unpasteurized fermented food to your pantry. (Plus, if you use a lot of soy sauce, you can save a lot of money with this one!)

What is Shoyu?

Shoyu is the Japanese term for the type of soy sauce that is made with both soybeans and wheat. It is normally what we are used to seeing when we think of “normal” soy sauce.

Shoyu differs from Tamari, another type of soy sauce, in that tamari uses little to no wheat and is sometimes fermented with a different strain of fungus (Aspergillus tamari). Tamari began as a byproduct of making soybean miso. It was the liquid that pooled up on the miso. Nowadays, though, with an increased demand for a wheat free soy sauce, companies work to make more tamari as a stand-alone product.

Is Soy Sauce Vegan?

People often ask this question, and the answer is Yes! Soy sauce is vegan.

Soy Sauce Ingredients

Soy sauce only uses soybeans, wheat, salt, water, and the strain of fungus desired for fermentation, normally Aspergillus oryzae or Aspergillus sojae. Aspergillus tamarii is sometimes used for making tamari.

On my very first attempt at making soy sauce, I went to the health food store and bought the only soybeans that were for sale at that particular store. They were small, green soybeans and didn’t make as nice of a paste or sauce.

I later saw that you could buy either larger white (beige) soybeans or the tiny green ones. It turns out that the beige soybeans are more mature soybeans, and the green soybeans are younger. The mature soybeans are the ones that are normally used to make everything from soy milk to, well, soy sauce.

How is Soy Sauce Made?

Homemade Soy Sauce (Shoyu)

Makes around 1 gallon

Ingredients

- 1200 g dry soybeans (the white or beige type)

- 1200 g wheat berries Soft wheat gives better flavor than hard wheat

- 7.5 g aspergillus orzyae starter meant for shoyu

For the Brine

- 825 g sea salt

- 3.8 liters water

Instructions

Prepare the soybeans

- Rinse the soybeans and cover them with water in a large glass jar or another suitable container. Keep in mind that they will double in size when they absorb the water.

- Soak them overnight, or for 12- 16 hours. (Add more water, as needed, to allow them to fully hydrate.) Notice in the photo that they have doubled in size once hydrated.

- Drain the soybeans and cook them by steaming them in a pressure cooker for an hour and a half, or cook them in boiling water for around 6 hours. A slow cooker is a good option in that case.

I used a pressure cooker and poured water in the bottom of the pressure cooker. I then put a stainless steel steamer basket over the water and filled the basket with the soaked soybeans. I set the pressure cooker to cook for an hour and a half.

- When fully cooked, you should be able to easily crush the soybeans with your fingers.

Prepare the wheat

- Brown the wheat berries in a skillet for several minutes until they turn golden brown. You can also broil them in the oven, spread over a baking sheet, stirring every couple of minutes to prevent burning, if you prefer.

- Grind the wheat coarsely using a food processor, grain mill, or another type of grinder. You are aiming to break each grain into several pieces. You don’t need to completely pulverize the wheat berries into powder.

Preparing the koji

- Mix together the ground wheat berries and the cooked, drained soybeans in a large mixing bowl. Allow the mixture to cool.

- Sprinkle a koji starter over the wheat and soy mixture and thoroughly incorporate it into the mixture.

- Spread the inoculated mixture over glass or stainless steel trays or bowls. (Use something with a broad base so that you can spread out the shoyu koji.)

Make furrows (small valleys) in the mixture every 2 inches or so to avoid having thick layers where hot spots emerge. (Hot spots are areas where the mold gives off too much heat.)

- Place a thermometer in the koji and cover the trays with either a plastic wrap or a tight weave cloth to help keep the moisture inside. Incubate the trays at around 85ªF (32ºC). (I used my oven with the oven light on to keep the temperature slightly elevated. You can also use hot water bottles or ice cold water bottles under the trays in an ice chest to raise or lower the temperature as needed.)

- Check the koji temperature every few hours to make sure it is staying in the 80-95ºF (27-35ºC) range. If the temperature gets too high for too long (over 104ºF (40ºC), unwanted bacteria can grow in the koji and spoil it. Each time you check on the koji, stir it, breaking up clumps as needed, and spread it out and add the furrows back in before covering and incubating again.

After 2- 2.5 days

- Continue to monitor the koji for 2 to 2 and a half days. You’ll notice that a fuzzy, soft white mold will cover the koji.

- It’s OK for some areas to begin to turn yellow or even a light yellow-green color. The yellowish green color is the formation of new koji spores. (Discard any koji that has grown black, or dark green mold. You also want to avoid any koji with shiny or sticky spots.)

Prepare the brine solution

- In a large glass container (around 2 gallons), mix together 1 gallon of filtered or spring water with 3.5 cups of sea salt. Stir until the salt has fully dissolved.

Prepare the moromi

- The moromi is the mixture of the koji and brine solution. Stir the koji into the brine solution and cover the mixture with a tight fitting lid. Label it with the date.

- Keep the moromi in a warm spot to continue to ferment. Stir the mixture daily for a week or so. After than, keep it in a warm spot (ideally around 77ºF (25ºC)), stirring it at least once a week for around 6 months.

- After around 6 months, you’ll notice that the color of the moromi will have darkened into a deep rust brown color. It may be either have separated into a liquid and solids (like mine) or be more or a homogenous thicker mixture.

Straining the moromi

- After 6-12 months fermentation, you’ll want to strain the moromi to obtain your homemade shoyu. The easiest way is probably to pour it into a cloth-lined strainer and pour some of the mixture into the strainer. You can then twist the cloth to press the filtered liquid through the cloth into a bottle.

- After around 9 months, around 3 months ago, I strained mine and it was a light, rust-colored liquid that tasted and smelled like soy sauce, but was much lighter in color.

- I was making homemade tamari at the same time (I’ll share that process soon- or as soon as I’m happy with the result), and this shows the 2 bottles I strained out 3 months ago. (I left the rest in the jar to continue fermentation there with the soybean and wheat mixture.)

Obtaining a dark-colored soy sauce

- One thing I had learned from my first failed attempts at making soy sauce was that one of the things that helped achieve a dark-colored soy sauce with complex flavors was to allow the sauce to ferment in the hot sun. So, I placed both bottles (of soy sauce and tamari) out in the hot sun from the end of June until the end of September. I was happy to see that both sauces had darkened with time out in the sun.

- You’ll notice that after 3 months outside in my sunny terrace, not only did they darken, but they also separated slightly leaving a bit of soy residue floating on top of the bottles. I strained the mixtures to obtain my sauces.

- I filtered the soy sauce again through a cloth to remove any soybean residue. The resulting liquid was a wonderfully dark colored shoyu with wonderful flavor.

Notes

What to do with the leftover soybean mash

While some people discard the soybean mash leftover after having strained out the soy sauce, others, like me, use it as they would miso in recipes.

Miso paste can be stirred into other sauces or mayonnaise to add a bit of saltiness and umami. It can be stirred into hot water, especially that boiled with seaweed varieties like kombu and wakame, to make a miso soup. The paste can also be added to stir fries.

Troubleshooting the soy sauce making process

My moromi is forming a mold on top

As a bit of an experiment, I had a separate jar of moromi fermenting that I left undisturbed. If you don’t stir the mixture very often, mold can form on top. After a bit of research, most soy sauce fermenters believed that it is OK to remove the top layer of mold and continue to ferment the sauce below.

In this case, the mold forming had the same colors and scent as the soy koji that I had made in the beginning, so I scraped peeled off the mold (it had a similar texture and held together as the koji had), continued to ferment the soy sauce, stirring occasionally. The resulting sauce didn’t appear any different than the other batch.

Use common sense here. If your moromi forms an unusual mold with a dark color or foul odor, while it may break your heart, you may be best to throw it away.

My moromi is forming a slimy layer

After having scraped off the moldy layer of my experimental batch of homemade soy sauce, I once again left it undisturbed. This time it didn’t form a mold, but instead formed a bit of a slimy layer on top. The top layer didn’t smell unpleasant, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to mix it in with the rest of the batch either.

My best guess is that this is some type of yeast that is forming on top. It gives off a yeast-y beer-like scent. Even though it wasn’t offensive, I scraped off most of the layer and mixed everything together again.

My soy sauce is too light in color

If I had only followed the instructions that came with my shoyu starter, I would have ended up with a dark amber colored soy sauce. In fact, most of my large batch still looks like the bottle above. (I took this picture this week of a bottle that I just strained.)

So, how did I end up getting such a beautifully dark soy sauce as shown in the first picture?

Well, two things help darken the soy sauce.

First, just filtering out any residual soybean paste will leave behind a darker color. After a couple of days, the soybean paste settled to the bottom, making the soy sauce look darker in color. To get it looking even darker, I filtered it through a tightly woven cotton cloth. You can see the huge difference in color already! It takes a bit of patience, but it’s worth the effort.

Second, it appears that one of the secrets to dark soy sauce is the same as the secret to dark skin in the summer… the sun!

The instructions that came with my starter never said anything about exposing the sauce to the sun, but through my earlier experimentation with making soy sauce using wild fungus, I learned that the sun may be your best friend when trying to make a dark, rich homemade soy sauce!

I read several accounts of people remembering their family members making soy sauce in Asia. They talked about the importance of using the sun, even to help prepare the brine for the koji. These people made the salt water ahead of time and allowed it to steep for several days in the sun before adding in the koji. They then proceeded to add the koji and allowed the mixture to ferment in the hot sun!

While I didn’t experiment with doing the whole fermenting process in the sun, I was a bit disappointed with the color of my homemade soy sauce, so I decided to experiment with leaving that outside in my terrace. I wasn’t sure if I’d be hurting the soy sauce, so I only strained out a small bottle and left it in a sunny part of my terrace for several weeks. (Looking at the dates on my photos, it appears that I actually left it there for almost 2 months.)

When it was time to take a look at it again, I was really happy to see how dark it had gotten. So, I’m now sunning out another bottle of soy and am tempted to bring out the whole unstrained batch!

Should you pasteurize your soy sauce?

It is said that pasteurization of the soy sauce will help extend its shelf life, and the cooking of the sauce helps to enhace its flavor and aroma. The idea is that you are killing off the bacteria in the sauce, and also beginning a Maillard reaction to deepen the flavor.

While that seems to be the general consensus, I’m not 100% sure if either of those statements is completely true. I’ve seen home brewers say that they like to leave half of their soy sauce unpasteurized because they think unpasteurized soy sauce has a more complex flavor profile. They pasteurize in the hopes of having their soy sauce last longer.

In a similar bit of skepticism, I really have to wonder if killing off the bacteria in the sauce will really extend its shelf life. When you make something like a homemade sauerkraut, some people say that the beneficial lactic acid bacteria that form also help preserve it. In fact, Leucidal, a natural preservative that I introduced when I shared how to make a lotion, uses Leuconostoc kimchii, a lactic acid bacteria formed when fermenting radishes, to restrict the growth of other microorganisms.

So, in the end, I’d say that experimenting and pasteurizing a small part of your batch is probably the best idea. That way you can decide if you prefer the flavor and aroma of unpasteurized soy sauce or not. You can also judge how long your sauce tastes best, and if you think that the pasteurized sauce lasts longer or not. I haven’t had mine for long enough to give you my opinion just yet…

I’ll try to update this post as I experiment with pasteurizing part of my batch.

How do you pasteurize soy sauce?

Cook the soy sauce at 160ºF (70ºC) for at least 30 minutes.

Does Soy Sauce Expire?

It takes between 6 months and a year to even be able to make a decent soy sauce. After that, it is usually said that soy sauce will last for around 3 years as long as you have it in sealed containers. It’s not necessarily that the soy sauce will “go bad” after that, but the quality of the sauce may deteriorate with time.

Here, again, I can’t speak from experience yet, and also have read accounts from home brewers who have said that their soy sauce has improved with time. Perhaps, here, the answer is it really depends on the batch, the method used for making the soy sauce, and your expectations of what makes a good soy sauce. Soy sauce may be like a good wine that improves with time- to a point! After a certain amount of time, some wines will begin to taste like vinegar. They aren’t toxic to drink, but they aren’t pleasant anymore either.

I’ll be keeping an eye on my own soy sauce, and will let you know my thoughts in a couple of years. Meanwhile, I’d love to hear from those of you with experience making your own soy sauce. 😉

Español

Español

Natural DIY Clarifying Shampoo

Natural DIY Clarifying Shampoo

David John

This boasts flavorful over chicken for a balanced meal choice.

Carolina Ramos

Excellent article, it was very simple to try! Thank you for all your work and sharing on the topic.

With your help, I have my soy sauce that is 12 months old and I was going to filter it now, however it smells like alcohol and not soy sauce, will cooking the sauce help? What could have gone wrong is that the sugar in the fermentation process was transformed into alcohol, but I don’t see any reference to this issue.

Can you please help me?

Tracy Ariza, DDS

Mine didn’t go through an alcoholic phase at all. Did you try to lower the salt content?

I believe it’s the salt brine that causes a different type of fermentation. You can “dehydrate” alcohol by salting it out. I’ve also never had sauerkraut or kimchi taste like alcohol.